January 21, 2018

Masters in the Field

Many think that creative nonfiction is a relatively new literary art form, but it is actually a tried and true approach to writing dramatic and memorable nonfiction, with a newish name.

There are many terrific examples of creative nonfiction from early on. Ernest Hemingway’s Death in the Afternoon, his paean to bullfighting, was published in 1931. Hemingway began his life as a journalist with two newspapers, the Kansas City Star and the Toronto Star, and wrote a number of cinematic stories about life on the frontlines during the first World War. His stories from those papers, his eyewitness dispatches from the front during the Spanish Civil War and World War II, and later his life in Cuba, published in Esquire, Colliers and Look, were collected in a terrific anthology edited by William White, by-line Ernest Hemingway.

Ernie Pyle, a Scripps Howard war correspondent, covered World War II from the points of view of the “dogface,” the ordinary infantry soldiers, from an intimate first-person perspective. He was a traditional newspaper reporter, syndicated in 300 papers across the U.S. and Canada, capturing the gritty life on the front lines with dramatic and memorable simplicity. I love this brief excerpt from a Pyle dispatch—this time not about the dogface but about the dogs who supported them.

“Always there are dogs in every invasion. There was a dog still on the beach, still pitifully looking for his masters. He stayed at the water’s edge, near a boat that lay twisted and half sunk at the waterline. He barked appealingly to every soldier who approached, trotted eagerly along with him for a few feet, and then, sensing himself unwanted in all the haste, he would run back to wait in vain for his own people at his own empty boat.”

George Orwell also covered the war, mostly from North Africa, for the British paper, the Observer. And long before the novels he is most known for, 1945’s Animal Farm and 1949’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell wrote two masterful immersion books of creative nonfiction. For the first, Down and Out in London and Paris (1933), he lived the life of near-destitution in Paris as a laborer in restaurant kitchens and, similarly, as a tramp in London.The Road to Wiggan Pier (1937) is his account of the hardships of working-class life in the Yorkshire and Lancashire.

Because she wrote mostly for the New Yorker, you don’t hear much about Lillian Ross who died not too long ago. But her Portrait of Hemingway (1950) and Picture her riveting account about the making of the film The Red Badge of Courage, originally appearing in the New Yorker, were published in book form, as well. Many other women writers were creative nonfiction pioneers, including, Ida Tarbell, Rachel Carson, Mary McCarthy, Joan Didion, Maya Angelo, Diane Ackerman, Jane Kramer, Annie Dillard and Susan Orlean.

Many of James Baldwin’s essays, some first appearing in Notes of a Native Son (1955), are not only masterfully written true stories, but confront issues that were, then, rarely discussed and examined: racial, sexual and cultural conflicts in the U.S. and abroad. Confronting similar issues plaguing our country, Alex Haley, better known for his Pulitzer Prize winning novel, Roots: The Saga of an American Family, co-authored The Autobiography of Malcolm X from a long series of interviews he conducted from 1963-1965, the year Malcolm X was assassinated.

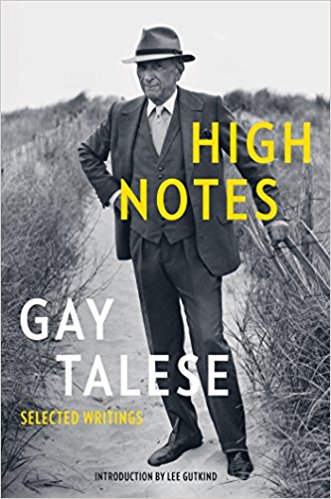

The “new journalists” came into vogue in the 1960s and 1970s due in large part to Tom Wolfe, who published a book of that title in 1973. It begins with a great introduction, documenting the genre, plus excerpts of true stories written by Truman Capote, Norman Mailer, Gay Talese, George Plimpton and Hunter Thompson to name a very few.

Talese, incidentally, named the “new journalism,” according to Wolfe. His 1966 classic profile, “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” was republished in the 70th anniversary issue of Esquire in October 2003, the editors calling the piece the “Best Story Esquire Ever Published.”

Here’s Gay Talese’s definition of the new journalism, taken from the introduction to Fame and Obscurity (1970), his collection of profiles of public figures, including Sinatra.

“Though often reading like fiction, it is not fiction. It is, or should be, as reliable as the most reliable reportage, although it seeks a larger truth than is possible through the mere compilation of verifiable facts, the use of direct quotations, and adherence to the rigid organizational style of the older form.”

Writers of creative nonfiction have been honored with prestigious literary prizes. Both Ernie Pyle and John McPhee have been awarded Pulitzers. And more recently Ta-Nehisi Coates won the National Book Award for Nonfiction in 2015 for Between the World and Me. Svetlana Alexievich, a Belarusian who writes creative nonfiction in Russian, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2015.

I could go on and on about the classics of creative nonfiction—then and now. Please share some of your favorites, books or essays that inspired you along your true story researching and writing journeys.

_____

Lee Gutkind is the author and editor of more than 30 books and founder and editor of Creative Nonfiction, the first and largest literary magazine to publish narrative nonfiction exclusively. He is Distinguished Writer-in-Residence in the Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes at Arizona State University and a professor in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society.