June 03, 2018

Tom Wolfe and the New Journalism Legacy

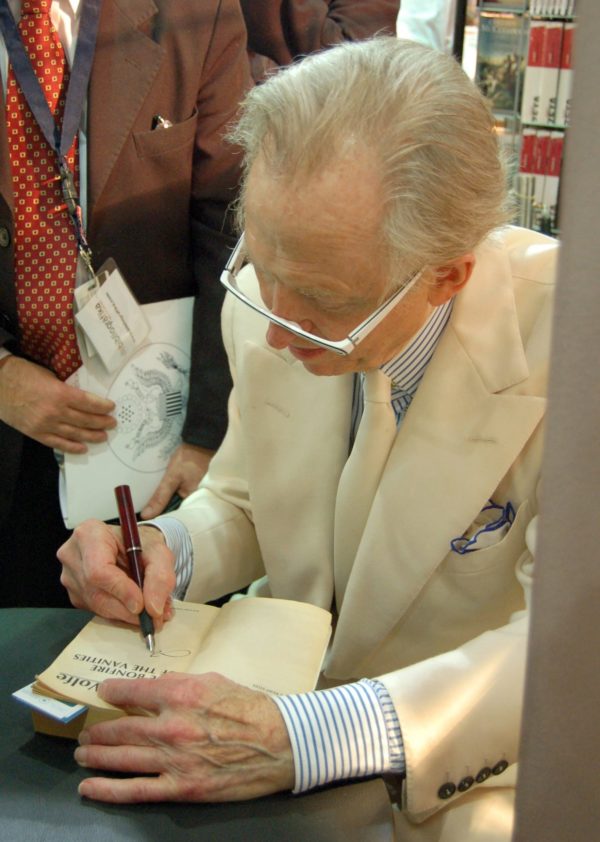

Tom Wolfe, signing an edition of “Bonfire of the Vanities” at the International Book Fair in Argentina.

[Photo by Wikimedia Commons]

Whether he liked the form or not, he knew, by promoting it, exactly what he was doing.

Wolfe was quite learned—he earned a PhD in American studies from Harvard, and his astute literary reflections and observations have been widely published—but he was a masterful self-promoter, demanding attention not only with his words, but his presentation, most famously his white linen suit. Especially in his younger days, it seemed to me, he set out to create dialogue and controversy for his own ends—an endeavor in which he was pretty damn successful.

But all Wolfe and other new journalists were really talking about with the “new journalism” was writing in scenes, using a lot of dialogue, writing with subjectivity—allowing a point of view, whether it be the writer’s or the character’s—and including what Wolfe called “status details,” meaning how people represent their positions in life through behavior and appearance (not unlike his own white suits!). Not that this wasn’t revolutionary and a game-changer in some quarters—the journalism community has, historically, been painfully and self-destructively resistant to change—but when you get down to the basics, new journalism meant being a very good writer who was willing to apply the diligence required for first-rate reporting, as well as having the time, patience, and talent to put all the information together in a powerful prose package.

One aspect Wolfe and others added, which was new to journalism, was their obsession with themselves; anything they felt, thought, dreamed, remembered seemed to be fair game, no matter how unrelated or uninteresting. Wolfe, in particular, loved the sound of his own voice, as in his “The Last American Hero” essay about stock car racer Junior Johnson, in which he sang:

Ten o’clock Sunday morning in the hills of North Carolina. Cars, miles of cars, in every direction, millions of cars, pastel cars, aqua green, aqua blue, aqua beige, aqua buff, aqua dawn, aqua dusk, aqua aqua, aqua Malacca, Malacca lacquer, Cloud lavender, Assassin pink, Rake-a-cheek raspberry. Nude Strand coral, Honest Thrill orange, and Baby Fawn Lust cream-colored cars are all going to the stock car races, and that old mothering North Carolina sun keeps exploding off the windshields. Mother dog!

This was cute—different—but such wailing wound through this essay and many others, including his book The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, and it sometimes wore thin. More troubling, according to critics back then, it provided substance for attacks about the new journalists’ self obsession and unnecessary verbosity and excesses, calling attention to their own voices rather than those they were writing about—thus distracting from the literary and journalistic value of the stories.

New journalism meant being a very good writer who was willing to apply the diligence required for first-rate reporting.

And these stories did have literary and journalistic value; they were rich in facts and carefully reported, but there was also a strong sense of style that was almost poetic in its vision. Wolfe sometimes took it a little too far; fortunately, the quirky innovations he introduced in some of his early work in New York Magazine and Esquire — writing in the accents of his characters, making up quotation marks like ::::::::::::::::::::::::, yelling and screaming at his readers IN CAPS—were gradually discarded. But done with a little restraint, this writing could be incredibly effective. Take, for instance, Norman Mailer’s incredible cataloging of characters and personas in Armies of the Night, for which he won the 1968 Pulitzer Prize in general nonfiction. Here we have Mailer describing the young people protesting the Vietnam War. He was appalled by their lack of a sense of history and how they treated political protest like a Halloween parade:

The hippies were there in great number, perambulating down the hill, many dressed like the legions of Sgt. Pepper’s Band, some were gotten up like Arab sheiks, or in Park Avenue doormen’s greatcoats, others like Rogers and Clark of the West, Wyatt Earp, Kit Carson, Daniel Boone in buckskin, some had grown mustaches to look like Have Gun – Will Travel—Paladin’s surrogate was here!—and wild Indians with feathers, a hippie gotten up like Batman, another like Claude Rains in The Invisible Man—his face wrapped in a turban of bandages and he wore a black satin top hat.

These stories did have literary and journalistic value; they were rich in facts and carefully reported, but there was also a strong sense of style that was almost poetic in its vision.

Not everyone was as thrilled and enthralled with this new(ish) style, however. As early as 1965, Dwight Macdonald, a writer, editor, and TV commentator, in reviewing Tom Wolfe’s The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby for TheNew York Review of Books, called it “parajournalism,” which, he wrote, “seems to be journalism . . . but the appearance is deceptive. It is a bastard form, having it both ways, exploiting the factual authority of journalism and the atmospheric license of fiction. Entertainment rather than information is the aim of its producers and the hope of its consumers.” Later, he complained, “We convert everything into entertainment,” and maybe he wasn’t too far off in his evaluation.

One could make the same argument today—that we value entertainment over information. Look, for instance, at the Internet, which puts an almost unimaginably vast world of information at our fingertips. I am not the first to point out that we have put a shameful amount of time into cluttering up this resource with videos and pictures of cats when, surely, we could be doing better, more important things with our time and technology. But, of course, entertainment and information needn’t be mutually exclusive. We understand that nonfiction needn’t be boring or laborious to be effective. It can and should entertain, inform, educate, and enlighten. Writing with truth and accuracy needn’t force a reader to pop the periodic NoDoz.

And I think that was the key to the success of new journalism—or whatever you want to call it. It was fun to read; it had energy, personality, authenticity, and pizzazz. And thanks in large part to Wolfe, this first-rate and sometimes experimental journalism had a name, whether he initially liked it or not, as well as a special persona—and that awakened nonfiction writers to the fact that the tools of our trade were limited only by our own inability or unwillingness to think and perform three-dimensionally. Wolfe’s new journalism doctrine provided an anchoring foundation to those who were working in this genre in the dark. Back then, when people asked what I wrote, I would say, “New journalism.” It sounded cool to me—and the thing is, it was cool. And it is cool. Although the label is out of favor now, it, along with Wolfe, inspired and powered the way in which we write nonfiction today.

– Adapted from Lee Gutkind’s “On the Fine Art of Literary Fist-Fighting,” published in the anthology, True Stories Well Told, From the First 20 Years of Creative Nonfiction Magazine.